I remember, at least eight years ago, during one of my casual discussions in his art studio in Chennai (Tamil Nadu, South India), C. Dakshinamoorthy had once mentioned that there are times when he gets absolutely entranced while creating his drawings, that he often but accidentally dips his paintbrush into his cup of tea instead of his bottle of ink. This, so lucidly and affably explains the modern master’s effervescent persona.

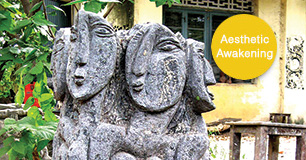

In 1943, Dakshinamoorthy was born in the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Indeed, it is significant to note that he had won the Indian National Award in 1985. Dakshinamoorthy is appreciated internationally, for his charismatic granite sculptures of the female human being, chiseled in an engaging, stylistic demeanor that is unquestionably cubist. Trained in the Government College of Arts and Crafts in Chennai (1960-1966), he was formerly the Head of the Department of Ceramics in the same college. As a British Council Scholar in 1978, he was schooled in Advanced Print-Making at the Croydon College of Design and Technology (the United Kingdom). From 1989 to 1991, this eminent master was awarded a Senior Fellowship by the Department of Culture, Government of India. As a spontaneous progression that synchronised with his consistent, high-spirited art-making, he moved on to participate in group and solo exhibitions in London, Argentina, Croydon, Australia and Singapore. His works were part of the 9th International Triennale of Coloured Graphic Prints in Switzerland (1982), and the 7th International Small Sculpture Exhibition of Budapest, Hungary (1987).

As we honour Dakshinamoorthy as a modern master, one question proves to be fundamentally important – whose ‘modern’ are we referring to? There are numerous specificities within the scope of modernity in art – the artist-specific, the nation-specific, the city-specific, the medium-specific, the technique-specific, the genre-specific, the event-specific and even the sentiment-specific. In the context of the art history of modern South India, the term ‘modern’ denotes, not a chronological reference to what is believed to be the period of modern art in the conveniently-general context (1800 to 1970s, in the European art-historical perspective), but a prudent combination of the genre-specific and the artist-specific perspectives.

C. Dakshinamoorthy, as a modern master, belongs to a generation of progressive artists of the late 1950s and the early 1960s in Madras (current Chennai), the artistic centre of South India. It was indeed a significant period in time in the modern art history of India in general and specifically South India, whereby artists were on an undaunted search or pursuit to express the modernity within their thoughts and inspirations via the embracement of the rich artistic tradition that they were readily endowed with in India. The nature of the modernity in the art that was created in South India (Madras, in particular) during this time was indeed a very purposeful, meticulously-conceived expression of traditional idioms in a grammar that was relatively new or from a perspective that was contextually or conceptually different from the norm. It is in this very spirit that the modern masters of South India embraced and continue to embrace the modernity in the art that they create so magnificently, bringing about a symbiosis between masterly renditions of technical skill within the framework of religio-mythological iconography and a strong sense of freedom in the re-contextualisation of traditional modes into a modern grammar, that quite effortlessly speaks to the viewer in the international arena.

An artistic tradition that does nothing to honour its living legends, is as good as non-existent. And so, let us sing joyful songs of glory for Dakshinamoorthy, as he relentlessly continues to create contemporary magic on granite – the stone that embodies the gods of his tradition.

To view artworks by C. Dakshinamoorthy, visit www.gnaniarts.com or email to

gnani_arts@yahoo.com.sg.

By Vidhya Gnana Gouresan